Chapter 7: Toasting, Trembling and Textiles on Quai Kellermann

“Earthquake,” stated Eirik around dawn the other day, calmly labeling the swaying of our fourth-floor apartment in downtown Strasbourg that I had not felt in my sleep until he mentioned it. The tremor ended up measuring over 3 on the Richter scale, up from a previous one a few months ago. Strasbourg is not on a fault line, and the buildings here were not constructed with earthquakes in mind. But the reason for this new seismic activity reflects a progressive effort to harness natural resources that goes back at least a century.

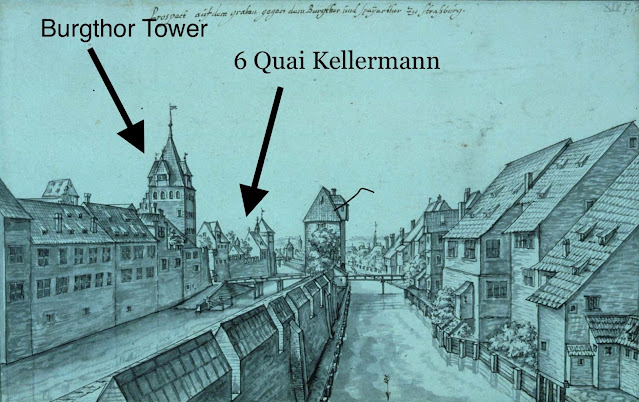

Located at the Northern end of the city’s main island, the neo-classical building where we rent an apartment on Quai Kellermann was constructed during one of Alsace’s German periods—between the end of the Franco-Prussian war in 1871 and the 1918 Treaty of Versailles handing the region back to France after World War I. Meaning ‘dock’ or ‘platform’, quai refers to our street’s location on the Southern bank of the now well-groomed canal de Faux-Rempart, which started out as an arm of the River Ill. Up until the 1830s, the river here was much wider, and buildings along this stretch dipped straight down into the water. In 1835, the city narrowed the canal and built platforms—or quais—to facilitate foot and road traffic in a ring around the narrow, winding alleys of the main city. Our quai was named for a revolutionary hero, native Strasbourgeois Kellermann, who employed a bold strategy to trick the Germans into abandoning their planned siege on Paris. Our building went up around 1900, apparently on the foundations of one of the generations of buildings that had lined this stretch of the river since Roman times.

|

| The wider River Ill and our block circa 1650 before platforms and roads were built |

|

| Burgthor Tower |

From our windows on the rear courtyard, we admire the often-chiming patina church tower, can spy on our neighbors in the surrounding buildings, and muse about a curious row of squat buildings below with their pitched tile roofs, round porthole windows and a prominent chimney. These little structures were apparently built in the late 19th century as a textile factory for a well-known lingerie company, Levy et Frères. As the “second Industrial revolution” began in the 1870s, the local economy picked up momentum, and factories proliferated all over Strasbourg. Many structures were patterned after naturally lit “weaving sheds” innovated in Britain, featuring a sawtooth roof design with windows on the Northern slope to maximize natural light and minimize heat. Once common throughout the city, this particular row of them is protected as the last remaining example in Strasbourg proper. The shed architectural style was phased out as electric lighting became more common, yet as interest in energy efficiency has increased, this design has been lauded and emulated in recent decades.

|

| Weaving sheds in our neighboring courtyard |

|

| Interior of factory today (a "concept" store) |

I value the widespread commitment to environmental sustainability in Europe, all over France and notably in Strasbourg. Building on this little example of its history of harnessing and preserving natural resources, Strasbourg is now the #1 biking city in France with extensive bike-friendly infrastructure that has substantially cut pollution in this river valley, while also making for healthier commuters and a quieter urban ambiance. Most impressively of all, the Strasbourg metropolitan area is striving to transition to renewable energy sources over the next three decades, aiming to reach 100% by the year 2050. Unfortunately, geothermic experimentation for renewable energy is the culprit behind the recent earthquakes. As such, the geothermic project had to be curtailed this year, and Strasbourg will have to return to the drawing board to innovate and adapt the city again to meet changing needs.

| Diagram of geothermic power production as done near Strasbourg (pumping hot water up, extracting the heat, and re-injecting the cold water back down, 1 km away) |

Last weekend, we enjoyed an evening with our neighbors in the courtyard at 6 Quai Kellermann. With the arrival of pleasant summer weather and Covid on a downward swing, I seized the first opportunity I’ve detected since our arrival last August to meet our neighbors at long last. Having deposited invitations in the anonymous bank of mailboxes, I wasn’t sure who would show. But as the church bells above us struck 6 pm, our fellow residents began emerging from their apartments bearing bottles, glasses and plates of appetizers. After nine months of wondering who else lived here, occasionally crossing paths and exchanging quick greetings in the stairway, and subconsciously weaving stories about fleeting faces behind Covid masks, it was like opening a new book that I’d been dying to read. I reveled in what turned into a leisurely evening of lively conversation, as we swapped earthquake experiences, discussed the factory sheds and church, and got to know each other beneath the huge, sheltering chestnut tree that reminds us so fondly of the one at our old rental house in Ardèche.

Post a comment