Chapter 4: Rainbows on Raven Bridge

In June 2021, I spontaneously joined Strasbourg’s Gay Pride march as it entered the historic town center via the Pont du Corbeau—Raven Bridge. After being canceled in 2020 due to the pandemic, the current ebb in Covid-19 cases enabled a scaled-down version this year of the usually huge and raucous Pride parade. Still, 7,000 revelers traversed the city with flags, signs and celebratory rainbow garb. My satisfaction in seeing so many people of all ages and stripes out embracing diversity, equality and love was underscored by what felt like our triumphant crossing of the Pont du Corbeau. This well-used bridge is marked by a history of intolerance and cruelty that is parallel to and probably overlaps with much of the world's treatment of gay, lesbian and trans people.

Pont du Corbeau is one of the more than 230 spans that make Strasbourg the French city with the most bridges. The main Southern entrance onto the big island of Strasbourg since before the 1300s, Pont du Corbeau spans the River Ill between the old meat market and slaughterhouse (near Suckling Pig Market square) on the main island, and on the other side: Place du Corbeau and the Krutenau neighborhood beyond. Known for centuries as Torture Bridge and for a time as Slaughterhouse Bridge, the bridge’s changing name over the years has consistently alluded to its sinister past.

|

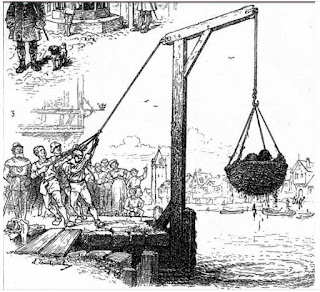

| Artist's rendering of the infamous Schandkorb on the Raven Bridge |

For hundreds of years, Pont du Corbeau was the site of public executions. Criminals of all kinds—petty thieves, murderers and quite often women accused of adultery, infanticide or witchcraft—were publicly shamed before being dipped or drowned in the putrid (and often frigid) waters below. The means of punishment changed over time—from a wooden plank off the bridge in the 14th and 15th centuries, to a hanging basket known as the “Schandkorb” in 1477, and from a sewn sack tossed from on high, to a submersible cage (thought somehow to be more humane?) in 1569. Eventually, a guillotine was used at the Place du Corbeau all the way until 1937. The person in charge of fishing cadavers out of the river with a hook was known as “the Raven,” giving the bridge its illustrious name since 1816.

The physical bridge itself has also changed over time, of course. For many centuries, it was a narrow, wooden footbridge. In the early 1800s, an ornate cast iron bridge replaced the wooden one, but the arc necessary to allow boats to pass beneath was found to be too steep for horse- and mule-drawn carriages to easily cross. So, in 1892, the current flat, stone bridge was constructed, originally with decorative pillars that were removed during the German occupation in 1942. For a long period, the bridge formed part of the main route from Paris to Vienna (though now that major highway skirts the central city). Today, the Pont du Corbeau remains a major thoroughfare shared by pedestrians, bikes and cars.

Adorned with flowers or Christmas decorations according to the season and spanning sparkling, cleanish and swan-dotted waters, the Raven Bridge’s dark past is not obvious to the casual observer. In warm weather, our family likes to walk over the bridge on the way through town from our apartment to a favorite ice cream shop. And during the holiday season, we escaped Covid confinement a few evenings each week to bask in the magical, sparkling stars strung from the bridge and nearby trees and to take in the festive light show projected on the old slaughterhouse walls above the dark, icy river.

The sharp contrast of this bridge’s hideous history with the bright, cheerful, bustle of its atmosphere now—and especially the exhilarating Pride march last weekend—is an encouraging reminder of humanity’s ability to emerge from dark times and to progress toward true justice. After our family returned home from the parade, we talked about how glad we are to live in a community where there is strong support for gender and sexual diversity, as well as activism in this and other important world issues. I also appreciate being in a place where evidence of the long road already traveled can fortify us to tackle the remaining obstacles.

Post a comment